Always mystify, mislead, and surprise the enemy, if possible; and when you strike and overcome him, never let up in the pursuit so long as your men have strength to follow; for an army routed, if hotly pursued, becomes panic-stricken, and can then be destroyed by half their number. The other rule is, never fight against heavy odds, if by any possible maneuvering you can hurl your own force on only a part, and that the weakest part, of your enemy and crush it. Such tactics will win every time, and a small army may thus destroy a large one in detail, and repeated victory will make it invincible.

General Thomas J. Jackson

True genius is a rarity on this planet, and it is amazing when it suddenly appears. Humans who display it often do so unexpectedly. So it was with Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson, nicknamed Stonewall, after the decisive role played by his forces at the battle of First Manassas (First Bull Run) in 1861. The name probably seemed appropriate to the few observers at the time who had followed his career. Jackson had a reputation as an unimaginative, albeit valiant, soldier. As a Professor of Natural Philosophy, Optics and Artillery Tactics (!) at VMI prior to the War he had a reputation as a deadly dull instructor who would repeat his lectures word for word if his students failed to grasp the lesson that he was teaching. He once spent a night in an office at VMI because his superior told him to wait for him, and then forgot about his appointment with Jackson. Other than his part in the victory at First Manassas, Jackson had distinguished himself mostly by being an almost fanatically strict disciplinarian. If genius were needed in the War, Jackson would not have been the man even those who admired him would turn to. Yes, the nickname Stonewall suited this stolid soldier.

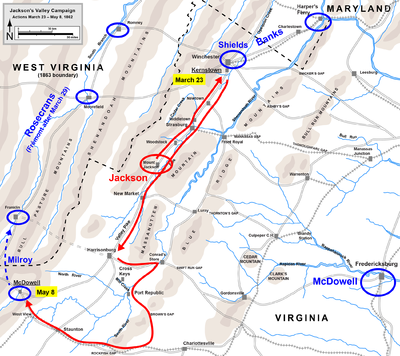

It took the Valley Campaign of 1862,where he outmarched and outfought numerous Union armies, each larger than the force he led, for Jackson to astonish North and South with the fact that behind this dull facade lurked one of the Great Captains of History.

Jackson opened the Campaign on March 23, 1862 with an attack on part of General Nathaniel Bank’s Union forces in the Shenandoah at Kernstown. Outnumbered almost three to one, Jackson suffered a tactical defeat but a strategic victory. This attack by a Confederate force so far north in the Valley and so close to Washington caused Lincoln to take a division from the Army of the Potomac and send it to the Shenandoah, to cancel any plans to reinforce the Army of the Potomac with troops from the Shenandoah and to order that McDowell’s corps would stay close to Washington during the ensuing Peninsula Campaign, rather than advancing overland towards Richmond to help McClellan on the Virginia Peninsula. Few defeats have been so beneficial as First Kernstown (there was a second battle of Kernstown during the 1864 Valley Campaign) was for the Confederacy.

The Valley Campaign now entered a long quiet period during which Jackson’s command skirmished with the various Union forces beginning to mass against his army. On May 7, 1862 Jackson saw an opportunity on the southwestern fringe of the Valley as Fremont’s men under General Robert Milroy, consisting of three regiments, were in an exposed position south of McDowell. Milroy on Shenandoah Mountain escaped an attempted encirclement by Jackson and withdrew to McDowell. There he was joined at 10:00 AM on May 8th, by Brigadier General Robert Schenck and his command that had arrived with after a forced march from Franklin, West Virginia. Schenck being senior took command of the combined force of approximately 6500 opposing Jackson’s army of 6000. Fighting continued until dark with the Union force, which had been on attack most of the day, withdrawing in good order. Casualties were fairly light: 259 for the Union (34 killed, 220 wounded, 5 missing), and for the Confederates 420 (116 killed, 300 wounded, 4 missing). It could be argued that tactically the battle was a draw, but in the following week the Union force retreated back to Franklin with Jackson pursuing all the way, returning to the Valley on May 15, 1862. This turned what was a tactical draw into a strategic victory. More posts on the Valley Campaign during this May and June. Here is Jackson’s report on the battle of McDowell:

GENERAL: I have the honor herewith to submit to you a report of the operations of my command in the battle of McDowell, Highland County, Virginia, on May 8:

After the battle of Kernstown I retreated in the direction of Harrisonburg. My rear guard– compromising Ashby’s cavalry, Captain Chew’s battery, and from time to time other forces– was placed under the direction of Col. Turner Ashby, an officer whose judgment, coolness, and courage eminently qualified him for the delicate and important trust Although pursued by a greatly superior force, under General Banks, we were enabled to halt for more than a fortnight in the vicinity of Mount Jackson.

After reaching Harrisonburg we turned toward the Blue Ridge, and on April 19 crossed the South Fork of the Shenandoah, and took position between that river and Swift Run Gap, in Elk Run Valley.

General R. S. Ewell, having been directed to join my command, left the vicinity of Gordonsville, and on the 30th arrived with his division west of the Blue Ridge.

The main body of General Banks’ pursuing army did not proceed farther south than the vicinity of Harrisonburg; but a considerable force, under the command of General Milroy, was moving toward Staunton from the direction of Monterey, and, as I satisfactorily learned, part of it had already crossed to the east of the Shenandoah Mountain, and was encamped not far from the Harrisonburg and Warm Springs turnpike. The positions of these two Federal armies were now such that if left unmolested they could readily form a junction on the road just named and move with their united forces against Staunton.

At this time Brig. Gen. Edward Johnson, with his troops, was near Buffalo Gap, west of Staunton, so that, if the enemy was allowed to effect a junction, it would probably be followed not only by the seizure of a point so important as Staunton, but must compel General Johnson to abandon his position, and he might succeed in getting between us. To avoid these results I determined, if practicable, after strengthening my own division by a union with Johnson’s, first to strike at Milroy and then to concentrate the forces of Ewell and Johnson with my own against Banks.

To carry out my design against Milroy General Ewell was directed to march his division to the position which I then occupied, in the Elk Run Valley, with a view to holding Banks in check, while I pushed on with my division to Staunton. These movements were made.

At Staunton I found, according to previous arrangements, Major-General Smith, of the Virginia Military Institute, with the corps of cadets, ready to cooperate in the defense of that portion of the valley.

On the morning of May 7 General Johnson, whose familiarity with that mountain region and whose high qualities as a soldier admirably fitted him for the advance, moved with his command in the direction of the enemy, followed by the brigades of General Taliaferro, Colonel Campbell, and General Winder, in the order named.

Encountering the enemy’s advance near the point where the Staunton and Parkersburg turnpike intersects the Harrisonburg and Warm Springs turnpike, General Johnson pressed forward. The Federals rapidly retreated, abandoning their baggage at Rodgers’ and other points east of the Shenandoah Mountain. After the advance had reached the western base of the Shenandoah Mountain the troops bivouacked for the night.

On the following morning the march was resumed, General Johnson’s brigade still in front. The head of the column was halted near the top of Bull Pasture Mountain, and General Johnson, accompanied by a party of 30 men and several officers, with a view to a reconnaissance of the enemy’s position, ascended Setlington’s Hill, an isolated spur of the Bull Pasture Mountain on the left of the turnpike, and commanding a full view of the village of McDowell. From this point the position, and to some extent the strength, of the enemy could be seen. In the valley in which McDowell is located was observed a considerable force of infantry. To the right, on a height, were two regiments, but too distant for an effective fire to that point. Almost a mile in front was a battery supported by infantry.

The enemy, observing a reconnoitering party, sent out a small body of skirmishers, which was promptly met by the men with General Johnson and driven back.

For the purpose of securing the hill, all of General Johnson’s regiments were sent to him. The Fifty-second Virginia Regiment, being the first to reach the ground, was posted on the left as skirmishers, and it was not long before they were engaged in a brisk encounter with the enemy’s skirmishers, whom they handsomely repulsed. Soon after this three other regiments arrived, and were posted as follows: The Twelfth Georgia on the crest of the hill, and forming the center of our line; the Fifty-eighth Virginia on the left, to support the Fifty-second, and the Forty-fourth Virginia on the right near a ravine.

Milky having during the day been re-enforced by General Schenck, determined to carry the hill, if possible, by a direct attack. Advancing in force along its western slope, protected in his advance by the character of the ground and the wood interposed in our front and driving our skirmishers before him, he emerged from the woods and poured a galling fire into our right, which was returned, and a brisk and animated contest was kept up for some time, when the two remaining regiments of Johnson’s brigade (the Twenty-fifth and Thirty-first) coming up, they were posted to the right. The fire was now rapid and well sustained on both sides and the conflict fierce and sanguinary.

In ascending to the crest of the hill from the turnpike the troops had to pass to the left through the woods by a narrow and rough route. To prevent the possibility of the enemy’s advancing along the turnpike and seizing the point where the troops left the road to ascend the hill. The Thirty-first Virginia Regiment was posted between that point and the town, and when ordered to join its brigade in action its place was supplied by the Twenty-first Virginia Regiment. The engagement had now not only become general along the entire line, but so intense, that I ordered General Taliaferro to the support of General Johnson. Accordingly, the Twenty-third and Thirty-seventh Virginia Regiments were advanced to the center of the line, which was then held by the Twelfth Georgia with heroic gallantry, and the Tenth Virginia was ordered to support the Fifty-second Virginia, which had already driven the enemy from the left and had now advanced to make a flank movement on him.

At this time the Federals were pressing forward in strong force on our extreme right, with a view of flanking that position. This movement of the enemy was speedily detected and met by General Taliaferro’s brigade and the Twelfth Georgia with great promptitude. Further to check it, portions of the Twenty-fifth and Thirty-first Virginia Regiments were sent to occupy an elevated piece of woodland on our right and rear, so situated as to fully command the position of the enemy. The brigade commanded by Colonel Campbell coming up about this time was, together with the Tenth Virginia, ordered down the ridge into the woods to guard against movements against our right flank, which they, in connection with the other force, effectually prevented.

The battle lasted about four hours-from 4.30 in the afternoon until 8.30. Every attempt by front or flank movement to attain the crest of the hill, where our line was formed, was signally and effectually repulsed. Finally, after dark, their force ceased firing, and the enemy retired.

The enemy’s artillery, posted on a hill in our front, was active in throwing shot and shell up to the period when the infantry fight commenced, but in consequence of the great angle of elevation at which they fired, and our sheltered position, they inflicted no loss upon our troops. Our own artillery was not brought up, there being no road to the rear by which our guns could be withdrawn in event of disaster, and the prospect of successfully using them did not compensate for the risk.

General Johnson, to whom I had entrusted the management of the troops engaged, proved himself eminently worthy of the confidence reposed in him by the skill, gallantry, and presence of mind which he displayed on the occasion. Having received a wound near the close of the engagement which compelled him to leave the field, he turned over the command to General Taliaferro.

During the night the Federals made a hurried retreat towards Franklin, in Pendleton County, leaving their dead upon the field. Before doing so, however, they succeeded in destroying most of their ammunition, camp equipage, and commissary stores, which they could not remove.

Official reports show a loss in this action of 71 killed and 390 wounded, making a total loss of 461.

Among the killed was Colonel Gibbons, of the Tenth Virginia Regiment. Colonel Harman, of the Fifty-second, Col. George H. Smith and Maj. John C. Higginbotham, of the Twenty-fifth, and Major Campbell, of the Forty-eighth Virginia, were among the wounded.

To prevent Banks from re-enforcing Milroy, Mr. J. Hotchkiss, who was on topographical duty with the army, proceeded with a party to blockade the roads through North River and Dry River Gaps, while a detachment of cavalry obstructed the road through Brock’s Gap.

As the Federals continued to fight until night and retreated before morning, but few of their number were captured. Besides quartermaster <ar15_473> and commissary stores, some arms and other ordnance stores fell into our hands.

Dr. Hunter McGuire, my medical director, managed his department admirably.

Lieut. Hugh H. Lee, chief of ordnance, rendered valuable assistance in seeing my instructions respecting the manner in which the troops should go into action faithfully carried out. I regret to say that during the action he was so seriously wounded as to render it necessary for him to leave the field.

First Lieut. A. S. Pendleton, aide-de camp; First Lieut. J. K. Boswell, chief engineer, and Second Lieut. R. K. Meade, assistant chief of ordnance, were actively engaged in transmitting orders.

Previous to the battle the enemy had such complete control of the pass through which our artillery would have to pass, if it continued to advance on the direct road to McDowell, that I determined to postpone the attack until the morning of the 9th. Owing to the action having been brought on by Milroy’s advancing to the attack on the 8th, Maj. R. L. Dabney, assistant adjutant-general, was not with me during the engagement.

Maj. J. A. Harman, chief quartermaster, and Maj. W. J. Hawks, chief commissary, had their departments in good condition.

Leaving Lieut. Col. J. T. L. Preston, with a detachment of cadets and a small body of cavalry, in charge of the prisoners and public property, the main body of the army, preceded by Capt. George Sheetz, with his cavalry, pursued the retreating Federals to the vicinity of Franklin, but succeeded in capturing only a few prisoners and stores along the line of march.

The junction between Banks and Milroy having been prevented, and becoming satisfied of the impracticability of capturing the defeated enemy, owing to the mountainous character of the country being favorable for a retreating army to make its escape, I determined, as the enemy had made another stand at Franklin, with a prospect of being soon re-enforced, that I would not attempt to press farther, but return to the open country of the Shenandoah Valley, hoping, through the blessing of Providence, to defeat Banks before he should receive re-enforcements.

On Thursday, the 15th, the army, after divine service, for the purpose of rendering thanks to God for the victory with which He had blessed us and to implore His continued favor, began to retrace its course.

Great praise is due the officers and men for their conduct in action and on the march.

Though Colonel Crutchfield, chief of artillery, did not have an opportunity of bringing his command into action on the 8th, it was used with effect on several occasions during the expedition.

My special thanks are due Maj. Gen. F. H. Smith for his conduct and patriotic co-operation during the expedition.

Col. T. H. Williamson, of the Engineers, rendered valuable service. For further information respecting the engagement and those who distinguished themselves I respectfully refer you to the accompanying reports of brigade and other commanders.

I am, general, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

T. J. JACKSON,

Lieutenant-General.

Brig. Gen. R. H. CHILTON,

I have copied Gen. Thomas Jackson’s warring advice. Seems good advice in any battle.

It is good advice in any type of conflict Mary. I have found it very helpful in my legal practice.