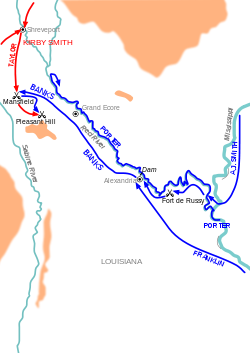

Something for the weekend. For Bales. A Confederate song mocking the defeat of the Union forces under Major General Nathaniel Banks, one of the more inept political generals, in 1864. The Red River campaign had as its objective the capture of Shreveport, Louisiana, in northwestern Louisiana, the largest city still under the control of the Confederates in the Pelican state, and the capture of hundreds of thousands of bales of cotton on plantations along the Red River. The bales of cotton were eagerly eyed by Union speculators and the entire campaign had an unsavory plundering feel to it. In any case the campaign ended in disaster for the Union, with the Union forces being beaten decisively at the battles of Mansfield and Pleasant Hill. Major General Richard Taylor, the only son of President Zachary Taylor, who commanded the Confederate forces in both engagements, was hailed as a hero of the Confederacy and promoted to Lieutenant General.

Here is a video of an extensive presentation by Dale Phillips on the Red River campaign:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPb5LR1goio

Here is the official report of the campaign by General Kirby Smith, the Confederate theater commander in the Trans-Mississippi:

HEADQUARTERS TRANS-MISSISSIPPI DEPARTMENT, Shreveport, June 11, 1864.

His Excellency JEFFERSON DAVIS, President Confederate States, Richmond, Va.

SIR: The history of the late campaign in this department will be made and forwarded as soon as the reports of the district commanders in Arkansas and Louisiana have been received. I desire, however, for the information of Your Excellency, to anticipate this report by a statement of facts bearing generally upon the campaign. Soon after my arrival in this department I became convinced that the valley of Red River was the only practicable line of operations by which the enemy could penetrate the country. This fact was well understood and appreciated by their generals.

In the latter part of August I received information that a formidable expedition was preparing under the auspices of Generals Grant and Banks. The main advance would be up Red River Valley, with subordinate columns moving from Helena and Berwick Bay. The defeat of Rosecrans at Chickamauga frustrated this plan. General Grant, with the larger portion of his command, was drawn to Tennessee. The columns from Helena and Berwick Bay moved, with what success has already been reported to the Department.

Feeling assured that the Red River expedition, so suddenly interrupted, would be renewed at some future day, I addressed myself to the task of meeting it with the slender means at my disposal. Fortifications were directed on the lower Red River. Shreveport and Camden were fortified, and works were ordered on the Sabine and the crossings of upper Red River. Depots were established on the shortest lines of communication between the Red River Valley and the troops serving in Arkansas and Texas. Those commands were directed to be held ready to move with little delay, and every preparation was made in advance for accelerating a concentration, at all times difficult, over long distances and through a country destitute of supplies and with limited means of transportation.

In February the enemy were preparing in New Orleans, Vicksburg, and Little Rock for offensive operations. Though 25,000 men were reported on the Texas coast, and though repeatedly urged to send troops to that district, my information convinced me that the valley of Red River would be the principal theater of operations, and that Shreveport would be the objective point of the columns moving from Arkansas and Louisiana. I continued steadily preparing for that event. On February 21, General Magruder was ordered to hold Green’s division of cavalry in readiness to move at a moment’s notice.

On March 5, he was telegraphed. (See No. 2191.) About that time the enemy commenced massing his forces at Berwick Bay. On March 12, General Magruder was telegraphed as follows. (See No. 2274.) On 15th, I received information of the enemy’s landing at Simsport. On March 18, the infantry of General Price’s command was by telegraph ordered to Shreveport.

The plan of campaign determined upon by me is indicated by the inclosed extracts from letters to Generals Price, Taylor, and Magruder.

The enemy were operating with a force of full 50,000 effective men. With the utmost powers of concentration not 25,000 men could be brought to meet their movements. Shreveport was made the point of concentration. With its fortifications, covering the depots, arsenals, and shops at Jefferson, Marshall, and above, it was a strategic point of vital importance. All the infantry not with Taylor opposed to Banks was directed to Shreveport. General Price, with his cavalry command, was instructed to delay the march of Steele’s column while the concentration was effected. Occupying a central position at Shreveport, with the enemy’s columns approaching from opposite directions, I proposed drawing -them to within striking distance, when, by concentrating upon and striking them in detail, both columns might be crippled or destroyed. (See extract from Taylor’s letters, M and N.)

On April 4, Churchill’s and Parsons’ divisions were ordered to Keachie, within supporting distance of General Taylor, at Mansfield. On the morning of April 5, I repaired to General Taylor’s headquarters at Mansfield, and on the afternoon of same day returned to Shreveport, from which point the operations of Generals Price and Taylor’s commands could best be directed.

In my interview with General Taylor at Mansfield on April 5, my plan of operations was distinctly explained. He agreed with me and expressed his belief that General Steele, being the bolder and more active, would advance sooner and more rapidly than Banks, and was the column first to be attacked.

General Taylor having reported the advance of the enemy’s cavalry to Pleasant Hill, on the morning of April 8, I wrote him the inclosed letter. His headquarters was between four and five hours by courier from Shreveport. The action was unexpectedly brought on by Mouton engaging the enemy at 5 o’clock in the evening of April 8.

I received General Taylor’s dispatch announcing the engagement at 4 o’clock on the morning of April 9, and rode 65 miles that day to Pleasant Hill, but did not reach there in time for the battle, which opened at 4 o’clock in the afternoon. On April 10, General Taylor returned with me to Mansfield, where the further operations of the campaign were discussed and determined upon by us. Banks was in full retreat, with the cavalry in pursuit. Our infantry was withdrawn by General Taylor to Mansfield for supplies. The country below Natchitoches had been completely desolated and stripped of supplies. The navigation of the river was obstructed, and even had our whole force been available for pursuit it could not have been subsisted below Natchitoches. General Steele was advancing, and to have pushed our whole force in pursuit of a fleeing enemy, while Steele’s column was in position to march upon our base and destroy our depots and shops, would have been sacrificing the advantages of our central position and abandoning the plan of campaign at the very time we were in position to have insured its success.

General Taylor agreed with me that the main body of our infantry should be pushed against Steele, and requested that he might accompany the column moving to Arkansas. He selected the troops that were to remain, placed General Polignac in command, and gave him his instructions for pushing the retreating army of General Banks.

On the morning of April 11, I returned to Shreveport and made preparations for the prosecution of the campaign in Arkansas. On April 14, I received information that Steele had turned the head of his column and was moving toward Camden. General Price was instructed that the infantry were moving to his support. He was ordered to throw his force within the fortifications at Camden if he believed himself strong enough to hold them against General Steele. (See 2687.) If too weak he was directed to throw a division of cavalry across the Ouachita and intercept all communication with and cut off all supplies going into Camden.

General Taylor arrived at Shreveport on the morning of April 16. I informed him that the change of Steele’s column and his march toward Camden had determined me in leaving him to conduct the operations on Red River, while in person I marched with the column moving to Arkansas; that should Steele retreat across the Ouachita the infantry column under my command would be turned at Minden and take the direct route to Campti, and thus be in time to operate against Banks’ retreating column.

In the mean time orders were given to remove the obstructions in Red River and to float the pontoon bridge down to Campti. Banks was reported fortifying at Grand Ecore; Steele about occupying our fortifications at Camden. His dislodgment was an absolute necessity. He threatened any movement down Red River against Banks. He held a strong base from which he could either unite with Banks at Grand Ecore or by a short line of march occupy Shreveport and destroy our shops, depots, and supplies while the army was operating on Red River below.

The infantry passed through Shreveport on April 16. I moved in person to the neighborhood of General Price’s headquarters. General Walker was halted at his camp, 19 miles from Minden, on April 20, 21, and 22. By reference to the map you will see that this was the strategic point from which he could be thrown rapidly to Camden, Campti, or Shreveport. The fortifications at Camden were too strong to be taken by assault. A few days’ delay in operations awaiting the arrival of the pontoon train was necessary. Minden, from its strategic position, was the point for detaining Walker during this delay.

On April 17, I made my headquarters near Calhoun, in telegraphic communication with Shreveport, and a few hours’ distance from General Price by courier. He here submitted to me his proposed attack upon the enemy’s train, which on April 18 resulted in the battle of Poison Springs, under General Maxey. On April 19, I found that General Price had not crossed any cavalry to the north side of the Arkansas River as directed, and that the day previous the enemy had received from Pine Bluff a commissary train of 200 wagons, guarded by an escort of 50 cavalry. I immediately organized an expedition of 4,000 picked cavalry, under General Fagan, who were ordered across the Ouachita, under instructions to destroy the supplies at Little Rock, Pine Bluff, and Devall’s Bluff, and then throw himself between the enemy and Little Rock. The destruction of these depots would have insured the loss of Steele’s entire army. Neither man nor beast could be sustained in the exhausted country between the Ouachita and White Rivers. The destruction of the enemy’s entire supply train and the capture of its escort at Marks’ Mills by General Fagan precipitated General Steele’s retreat from Camden. He evacuated the place on the morning of April 27. By a forced march of 42 miles we overtook him at Saline Bottom on the morning of April 30. Our troops marched through mud and rain during the previous night and attacked under great disadvantages–tired, exhausted, with mud and water up to their knees and waists. Marmaduke’s brigade of cavalry, dismounted as skirmishers, opened the fight, and were hotly engaged through the morning. The battle closed at 1 o’clock, a complete victory; the enemy leaving his dead, wounded, wagons, &c., on the field. The rise of the river, which flooded the bottom for some miles, and the exhausted condition of our men prevented pursuit. Marmaduke’s brigade was the only cavalry with me.

On the evacuation of Camden, General Maxey, with his command, had been ordered back to the Indian country, where the movements of the enemy imperatively demanded his presence. Had General Fagan, with his command, thrown himself on the enemy’s front on his march from Camden, Steele would have been brought to battle and his command utterly destroyed long before he reached the Saline. I do not mean to censure General Fagan. That gallant officer taking the road to Arkadelphia after the battle of Marks’ Mills was one of those accidents which are liable to befall the best of officers. After the battle of Jenkins’ Ferry the infantry divisions of Churchill, Parsons, and Walker were marched by the most direct route to Louisiana, with orders to report to General Taylor. The evacuation of Alexandria and the reoccupation of the lower Red River Valley closed the campaign.

I understand that efforts have been made in Richmond to have me relieved from command of the department. I know that facts will be misrepresented and distorted by certain parties in Louisiana who are waging a bitter war against me. I have made a plain statement in advance of my reports that Your Excellency might have the means of judging impartially of past events.

While I believe that my operations in the late campaign, founded on true military principles, have been productive of at least as great results as would have been achieved by a different course, I do not ask to be retained in command, but will gladly and cheerfully yield to a successor whenever it is deemed the interests of the service require a change.

Respectfully and faithfully, your obedient servant,

E. KIRBY SMITH, General.