“Non nobis Domine! non nobis sed nomini tuo da gloriam.”

General William S. Rosecrans at the end of his report on the battle of Stones River, attributing the Union victory to God.

An unjustly obscure battle of the Civil War began 150 years ago today: Stones River. Based on the number of combatants involved, it was the bloodiest battle fought in an extremely bloody War. The two armies involved, the Union Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of Tennessee, were struggling for control of middle Tennessee. If the Confederate Army of Tennessee could be chased out of middle Tennessee, then Union control of Nashville was secure, and it could be used as a springboard for the conquest of southeastern Tennessee and the eventual invasion of Georgia. If the Union Army of the Cumberland could be defeated, then Nashville might fall, and the Confederate heartland be secured from invasion. The stakes were high at Stones River. A critical factor for the Union was that morale in the North was plummeting. The Army of the Potomac had suffered a shattering defeat a few weeks before at Fredericksburg, and Grant and his Army of the Tennessee seemed to be stymied by the Confederate fortress city of Vicksburg. The War for the Union seemed to be going no place at immense cost in blood and treasure. If the Army of the Cumberland led by General Rosecrans was defeated, voices raised in the North to “let the erring sisters go” might swell into a chorus that would lead eventually to a negotiated peace, especially after election losses for the Republicans in the Congressional elections already demonstrated deep dissatisfaction in the North as to the progress of the War.

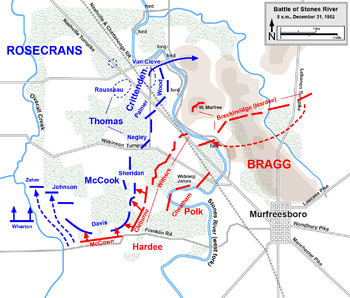

General Rosecrans led the Army of the Cumberland out of Nashville the day after Christmas and marched southeast 40 miles to challenge the Army of Tennessee at Murfreesboro. The armies were comparable in size with the Army of the Cumberland having 41,000 men opposed to the 35,000 of the Army of the Tennessee. Both Rosecrans and Bragg planned to attack the opposing army by attacking its right flank. On December 31, Bragg struck first.

Confederate General William J. Hardee led his corps in a slashing attack at 8:00 AM against General Alexander M. McCook’s corps, and by 10:00 AM had chased the Union troops back three miles before they rallied. Rosecrans cancelled the attack against the Confederate right by General Thomas L. Crittenden’s corps, and rushed reinforcements to his embattled right. Confederate General Leonidas Polk, an Episcopalian bishop in civilian life, launched simultaneous attacks against the left of McCook’s corp. Here General Phil Sheridan’s division put up a stout resistance, but was eventually driven back.

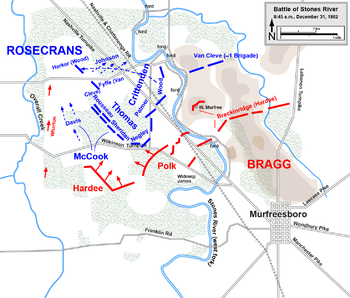

By late morning the Union army had its back to Stones River and its line perpendicular on its right to its original position. Rosecrans, who seemed to be everywhere on the battlefield that day, succeeded in rallying his troops. The left of the Union line held against repeated assaults, the fiercest fighting centering on a four-acre wooded tract, known until the battle as the Round Forest, held by Colonel William B. Hazen’s brigade. The ferocity of the fighting can be judged by the fact that after the battle the tract of land would ever be known as Hell’s Half Acre. The Union forces held and by 4:30 PM. winter darkness brought an end to that day’s fighting.

Rosecrans held a council of war that night to determine if the army should stand or retreat. General George H. Thomas who had led his corps in the center with his customary skill and determination made the laconic comment that “There is no better place to die” and Rosecrans readily agreed. The Army of the Cumberland would stand and fight.

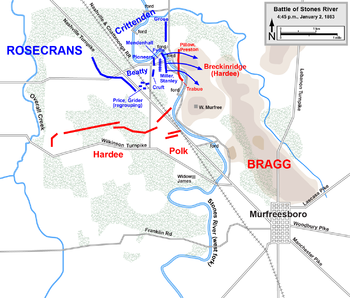

Bragg believed that he had won a victory and with caused due to the success of his initial attacks. He was content to wait for Rosecrans to admit defeat and retreat. There was only skirmishing between the armies on New Year’s Day, each force content to tend its wounded while keeping a wary eye on their adversaries.

Bragg on January 2, tired of waiting for Rosecrans to retreat, ordered General John C. Breckinridge, a former Vice-President of the United States to attack a hill in front of the Union center with his division. Breckinridge protested that an attack would be suicidal. When Bragg overruled his protest Breckinridge attacked. Thomas repulsed the attack with heavy Confederate loss.

On January 3, Rosecrans received a supply train and reinforcements. With the odds against him increasing, Bragg order the retreat of his army which commenced at 10:30 PM on the evening of January 3. Casualties in killed and wounded were approximately 12,000 on each side.

The news of the victory was trumpeted across the North and banished the atmosphere of gloom and defeat that had enveloped the nation. The importance of this victory was underlined by Lincoln in a letter to Rosecrans: “I can never forget, whilst I remember anything, that about the end of last year and the beginning of this, you gave us a hard-earned victory, which, had there been a defeat instead, the nation could scarcely have lived over.” Here is the official report of the battle by General Rosecrans:

HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE CUMBERLAND, Murfreesborough, Tenn., February 12, 1863.

Brig. Gen. LORENZO THOMAS, Adjutant-General, U. S. Army.

GENERAL: As the sub-reports are now nearly all in, I have the honor to submit, for the information of the General-in-Chief, the subjoined report, with accompanying sub-reports, maps, and statistical tables of the battle of Stone’s River. To a proper understanding of this battle it will be necessary to state the preliminary movements and preparations: Assuming command of the army at Louisville on October 27, it was found concentrated at Bowling Green and Glasgow, distant about 113 miles from Louisville, from whence, after replenishing with ammunition, supplies, and clothing, they moved on to Nashville, the advance corps reaching that place on the morning of November 7, a distance of 183 miles from Louisville. At this distance from my base of supplies, the first thing to be done was to provide for the subsistence of the troops and open the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. The cars commenced running through on November 26, previous to which time our supplies had been brought by rail to Mitchellsville, 35 miles north of Nashville, and from thence, by constant labor, we had been able to haul enough to replenish the exhausted stores for the garrison at Nashville and subsist the troops of the moving army.

From November 26 to December 26 every effort was bent to complete the clothing of the army; to provide it with ammunition, and replenish the depot at Nashville with needful supplies; to insure us against want from the largest possible detention likely to occur by the breaking of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, and to insure this work the road was guarded by a heavy force posted at Gallatin. The enormous superiority in numbers of the rebel cavalry kept our little cavalry force almost within the infantry lines, and gave the enemy control of the entire country around us. It was obvious from the beginning that we should be confronted by Bragg’s army, recruited by an inexorable conscription, and aided by clans of mounted men, formed into a guerrilla-like cavalry, to avoid the hardships of conscription and infantry service. The evident difficulties and labors of an advance into this country, and against such a force, and at such distance from our base of operations, with which we were connected but by a single precarious thread, made it manifest that our policy was to induce the enemy to travel over as much as possible of the space that separated us, thus avoiding for us the wear and tear and diminution of our forces, and subjecting the enemy to all this inconvenience, besides increasing for him and diminishing for us the dangerous consequences of a defeat. The means taken to obtain this end were eminently successful. The enemy, expecting us to go into winter quarters at Nashville, had prepared his own winter quarters at Murfreesborough, with the hope of possibly making them at Nashville, and had sent a large cavalry force into West Tennessee to annoy Grant, and another large force into Kentucky to break up the railroad.

In the absence of these forces, and with adequate supplies in Nashville, the moment was judged opportune for an advance on the rebels. Polk’s and Kirby Smith’s forces were at Murfreesborough, and Hardee’s corps on the Shelbyville and Nolensville pike, between Triune and Eagleville, with an advance guard at Nolensville, while our troops lay in front of Nashville, on the Franklin, Nolensville, and Murfreesborough turnpikes.

The plan of the movement was as follows: McCook, with three divisions, to advance by Nolensville pike to Triune. Thomas, with two divisions (Negley’s and Rousseau’s), to advance on his right, by the Franklin and Wilson pikes, threatening Hardee’s right, and then to fall in by the cross-roads to Nolensville. Crittenden, with Wood’s, Palmer’s, and Van Cleve’s divisions, to advance by the Murfreesborough pike to La Vergne.

With Thomas’ two divisions at Nolensville, McCook was to attack Hardee at Triune, and, if the enemy re-enforced Hardee, Thomas was to support McCook. If McCook beat Hardee, or Hardee retreated, and the enemy met us at Stewart’s Creek, 5 miles south of La Vergne, Crittenden was to attack him, Thomas was to come in on his left flank, and McCook, after detaching a division to pursue or observe Hardee, if retreating south, was to move with the remainder of his force on their rear. The movement began on the morning of December 26. McCook advanced on the Nolensville pike, skirmishing his way all day, meeting with stiff resistance from cavalry and artillery, and closing the day by a brisk fight, which gave him possession of Nolensville and the hills 1½ miles in front, capturing one gun by the One hundred and first Ohio and Fifteenth Wisconsin Regiments, his loss this day being about 75 killed and wounded. Thomas followed on the right, and closed Negley’s division on Nolensville, leaving the other (Rousseau’s) division on the right flank. Crittenden advanced to La Vergne, skirmishing heavily on his front, over a rough country, intersected by forests and cedar brakes, with but slight loss.

On the 28th [27th] General McCook advanced on Triune, but his movement was retarded by a dense fog.

Crittenden had orders to delay his movements until McCook had reached Triune and developed the intentions of the enemy at that point, so that it could be determined which Thomas was to support.

McCook arrived at Triune, and reported that Hardee had retreated, and that he had sent a division in pursuit.

Crittenden began his advance about 11 a.m., driving before him a brigade of cavalry, supported by Maney’s brigade of rebel infantry, and reached Stewart’s Creek, the Third Kentucky gallantly charging the rear guard of the enemy, and saving the bridge, on which had been placed a pile of rails that had been set on fire. This was Saturday night.

McCook having settled the fact of Hardee’s retreat, Thomas moved Negley’s division on to join Crittenden at Stewart’s Creek, and moved Rousseau’s to Nolensville.

On Sunday the troops rested, except Rousseau’s division, which was ordered to move on to Stewartston, and Willich’s brigade, which had pursued Hardee as far as Riggs’ Cross.Roads, and had determined the fact that Hardee had gone to Murfreesborough, when they returned to Triune.

On Monday morning, McCook was ordered to move from Triune to Wilkinson’s Cross-Roads, 6 miles from Murfreesborough, leaving a brigade at Triune. Crittenden crossed Stewart’s Creek by the Smyrna Bridge and the main Murfreesborough pike, and Negley by the ford 2 miles above; their whole force to advance on Murfreesborough, distant about 11 miles. Rousseau was to remain at Stewart’s Creek until his train came up, and prepare himself to follow. McCook reached Wilkinson’s Cross-Roads by evening, with an advance brigade at Overall’s Creek, saving and holding the bridge, meeting with but little resistance. Crittenden’s corps advanced, Palmer leading, on the Murfreesborough pike, followed by Negley, of Thomas’ corps, to within 3 miles of Murfreesborough, having had several brisk skirmishes, driving the enemy rapidly, saving two bridges on the route, and forcing the enemy back to his intrenchments.

About 3 p.m. a signal message coming from the front, from General Palmer, that he was in sight of Murfreesborough, and that the enemy were running, an order was sent to General Crittenden to send a division to occupy Murfreesborough. This led General Crittenden, on reaching the enemy’s front, to order Harker’s brigade to cross the river at a ford on his left, where he surprised a regiment of Breckinridge’s division and drove it back on its main line, not more than 500 yards distant, in considerable confusion; and he held this position until General Crittenden was advised, by prisoners captured by Harker’s brigade, that Breckinridge was in force on his front, when, it being dark, he ordered the brigade back across the river, and reported the circumstances to the commanding general on his arrival, to whom he apologized for not having carried out the order to occupy Murfreesborough. The general approved of his action, of course, the order to occupy Murfreesborough having been based on the information received from General Crittenden’s advance division that the enemy were retreating from Murfreesborough.

Crittenden’s corps, with Negley’s division, bivouacked in order of battle, distant 700 yards from the enemy’s intrenchments, our left extending down the river some 500 yards. The Pioneer Brigade, bivouacking still lower down, prepared three fords, and covered one of them, while Wood’s division covered the other two, Van Cleve’s division being in reserve.

On the morning of the 30th, Rousseau, with two brigades, was ordered down early from Stewart’s Creek, leaving one brigade there and sending another to Smyrna to cover our left and rear, and took his place in reserve, in rear of Palmer’s right, while General Negley moved on through the cedar brakes until his right rested on the Wilkinson pike, as shown by the accompanying plan. The Pioneer Corps cut roads through the cedars for his ambulances and ammunition wagons.

The commanding general remained with the left and center, examining the ground, while General McCook moved forward from Wilkinson’s Cross-Roads, slowly and steadily, meeting with heavy resistance, fighting his way from Overall’s Creek until he got into position, with a loss of some 135 killed and wounded.

Our small division of cavalry, say 3,000 men, had been divided into three parts, of which General Stanley took two and accompanied General McCook, fighting his way across from the Wilkinson to the Franklin pike, and below it, Colonel Zahm’s brigade leading gallantly, and meeting with such heavy resistance that McCook sent two brigades from Johnson’s division, who succeeded in fighting their way into the position shown on the accompanying plan, marked A, while the third brigade, which had been left at Triune, moved forward from that place, and arrived at nightfall near General McCook’s headquarters. Thus, on the close of the 30th, the troops had all get into the position, substantially., as shown in the accompanying drawing, the rebels occupying the position marked A.

At 4 o’clock in the afternoon General McCook had reported his arrival on the Wilkinson pike, joining Thomas; the result of the combat in the afternoon near Griscom’s house, and the fact that Sheridan was in position there; that his right was advancing to support the cavalry; also that Hardee’s corps, with two divisions of Polk’s, was on his front, extending down toward the Salem pike, without any map of the ground, which was to us terra incognita. When General McCook informed the general commanding that his corps was facing strongly toward the east, the general commanding told him that such a direction to his line did not appear to him a proper one, but; that it ought, with the exception of his left, to face much more nearly south, with Johnson’s division in reserve, but that this matter must be confided to him, who knew the ground over which he had fought.

A meeting of the corps commanders was called at the headquarters of the commanding general for this evening. General Thomas arrived early, received his instructions, and retired. General Crittenden, with whom the commanding general had talked freely during the afternoon, was sent for, but was excused at the request of his chief of staff, who sent word that he was very much fatigued and was asleep. Generals McCook and Stanley arrived about 9 o’clock, to whom was explained the following

PLAN OF BATTLE.

McCook was to occupy the most advantageous position, refusing his right as much as practicable and necessary to secure it, to receive the attack of the enemy; or, if that did not come, to attack himself, sufficient to hold all the force on his front; Thomas and Palmer to open with skirmishing, and engage the enemy’s center and left as far as the river; Crittenden to cross Van Cleve’s division at the lower ford, covered and supported by the sappers and miners, and to advance on Breckinridge; Wood’s division to follow by brigades, crossing at the upper ford and moving on Van Cleve’s right, to carry everything before them into Murfreesborough. This would have given us two divisions against one, and, as soon as Breckinridge had been dislodged from his position, the batteries of Wood’s division, taking position on the heights east of Stone’s River, in advance, would see the enemy’s works in reverse, would dislodge them, and enable Palmer’s division to press them back, and drive them westward across the river or through the woods, while Thomas, sustaining the movement on the center, would advance on the right of Palmer, crushing their right, and Crittenden’s corps, advancing, would take Murfreesborough, and then, moving westward on the Franklin road, get in their flank and rear and drive them into the country toward Salem, with the prospect of cutting off their retreat and probably destroying their army.

It was explained to them that this combination, insuring us a vast superiority on our left, required for its success that General McCook should be able to hold his position for three hours; that, if necessary to recede at all, he should recede, as he had advanced on the preceding day, slowly and steadily, refusing his right, thereby rendering our success certain.

Having thus explained the plan, the general commanding addressed General McCook as follows: “You know the ground; you have fought over it; you know its difficulties. Can you hold your present position for three hours? To which General McCook responded, “Yes, I think I can.” The general commanding then said, 6, I don’t like the facing so much to the east, but must confide that to you, who know the ground. If you don’t think your present the best position, change it. It is only necessary for you to make things sure.” And the officers then returned to their commands.

At daylight on the morning of the 31st the troops breakfasted and stood to their arms, and by 7 o’clock were preparing for the

BATTLE

The movement began on the left by Van Cleve, who crossed at the lower fords. Wood prepared to sustain and follow him. The enemy, meanwhile, had prepared to attack General McCook, and by 6.30 o’clock advanced in heavy columns–regimental front–his left attacking Willich’s and Kirk’s brigades, of Johnson’s division, which, being disposed, as shown in the map, thin and light, without support, were, after a sharp but fruitless contest, crumbled to pieces and driven back, leaving Edgarton’s and part of Goodspeed’s battery in the hands of the enemy.

The enemy following up, attacked Davis’ division and speedily dislodged Post’s brigade. Carlin’s brigade was compelled to follow, as Woodruff’s brigade, from the weight of testimony, had previously left its position on his left. Johnson’s brigades, in retiring, inclined too far to the west, and were too much scattered to make a combined resistance, though they fought bravely at one or two points before reaching Wilkinson’s pike. The reserve brigade of Johnson’s division, advancing from its bivouac, near the Wilkinson pike, toward the right, took a good position, and made a gallant but ineffectual stand, as the whole rebel left was moving up on the ground abandoned by our troops.

Within an hour from the time of the opening of the battle, a staff officer from General McCook arrived, announcing to me that the right wing was heavily pressed and needed assistance; but I was not advised of the rout of Willich’s and Kirk’s brigades, nor of the rapid withdrawal of Davis’ division, necessitated thereby–moreover, having supposed his wing posted more compactly, and his right more refused than it really was, the direction of the noise of battle did not indicate to me the true state of affairs. I consequently directed him to return and direct General McCook to dispose his troops to the best advantage, and to hold his ground obstinately. Soon after, a second officer from General McCook arrived, and stated that the right wing was being driven–a fact that was but too manifest by the rapid movement of the noise of battle toward the north.

General Thomas was immediately dispatched to order Rousseau, then in reserve, into the cedar brakes to the right and rear of Sheridan. General Crittenden was ordered to suspend Van Cleve’s movement across the river, on the left, and to cover the crossing with one brigade, and move the other two brigades westward across the fields toward the railroad for a reserve. Wood was also directed to suspend his preparations for crossing, and to hold Hascall in reserve. At this moment fugitives and stragglers from McCook’s corps began to make their appearance through the cedar-brakes in such numbers that I became satisfied that McCook’s corps was routed. I, therefore, directed General Crittenden to send Van Cleve in to the right of Rousseau; Wood to send Colonel Harker’s brigade farther down the Murfreesborough pike, to go in and attack the enemy on the right of Van Cleve’s, the Pioneer Brigade meanwhile occupying the knoll of ground west of Murfreesborough pike, and about 400 or 500 yards in rear of Palmer’s center, supporting Stokes’ battery (see accompanying drawing). Sheridan, after sustaining four successive attacks, gradually swung his right from a southeasterly to a northwesterly direction, repulsing the enemy four times, losing the gallant General Sill, of his right, and Colonel Roberts, of his left brigade, when, having exhausted his ammunition, Negley’s division being in the same predicament, and heavily pressed, after desperate fighting, they fell back from the position held at the commencement, through the cedar woods, in which Rousseau’s division, with a portion of Negley’s and Sheridan’s, met the advancing enemy and checked his movements.

The ammunition train of the right wing, endangered by its sudden discomfiture, was taken charge of by Captain Thruston, of the First Ohio Regiment, ordnance officer, who, by his energy and gallantry, aided by a charge of cavalry and such troops as he could pick up, ear-tied it through the woods to the Murfreesborough pike, around to the rear of the left wing, thus enabling the troops of Sheridan’s division to replenish their empty cartridge-boxes. During all this time Palmer’s front had likewise been in action, the enemy having made several attempts to advance upon it. At this stage it became necessary to readjust the line of battle to the new state of affairs. Rousseau and Van Cleve’s advance having relieved Sheridan’s division from the pressure, Negley’s division and Cruft’s brigade, from Palmer’s division, withdrew from their original position in front of the cedars, and crossed the open field to the east of the Murfreesborough pike, about 400 yards in rear of our front line, where Negley was ordered to replenish his ammunition and form in close column in reserve.

The right and center of our line now extended from Hazen, on the Murfreesborough pike, in a northwesterly direction; Hascall supporting Hazen; Rousseau filling the interval to the Pioneer Brigade; Negley in reserve; Van Cleve west of the Pioneer Brigade; McCook’s corps refused on his right, and slightly to the rear, on Murfreesborough pike; the cavalry being still farther to the rear, on Murfreesborough pike, at and beyond Overall’s Creek.

The enemy’s infantry and cavalry attack on our extreme right was repulsed by Van Cleve’s division, with Harker’s brigade and the cavalry. After several attempts of the enemy to advance on this new line, which were thoroughly repulsed, as were also their attempts on the left, the day closed, leaving us masters of the original ground on our left, and our new line advantageously posted, with open ground in front, swept at all points by our artillery.

We had lost heavily in killed and wounded, and a considerable number in stragglers and prisoners; also twenty-eight pieces of artillery, the horses having been slain, and our troops being unable to with draw them by hand over the rough ground; but the enemy had been thoroughly handled and badly damaged at all points, having had no success where we had open ground and our troops were properly posted: none which did not depend on the original crushing in of our right and the superior masses which were in consequence brought to bear upon the narrow front of Sheridan’s and Negley’s divisions, and a part of Palmer’s, coupled with the scarcity of ammunition, caused by the circuitous road which the train had taken, and the inconvenience of getting it from a remote distance through the cedars. Orders were given for the issue of all the spare ammunition, and we found that we had enough for another battle, the only question being where that battle was to be fought.

It was decided, in order to complete our present lines, that the left should be retired some 250 yards to a more advantageous ground, the extreme left resting on Stone’s River, above the lower ford, and extending to Stokes’ battery. Starkweather’s and Walker’s brigades arriving near the close of the evening, the former bivouacked in close column, in reserve, in rear of McCook’s left, and the latter was posted on the left of Sheridan, near the Murfreesborough pike, and next morning relieved Van Cleve, who returned to his position in the left wing.

DISPOSITION FOR JANUARY 1, 1863

After careful examination and free consultation with corps commanders, followed by a personal examination of the ground in rear as far as Overall’s Creek, it was determined to await the enemy’s attack in that position; to send for the provision train, and order up fresh supplies of ammunition; on the arrival of which, should the enemy not attack, offensive operations were to be resumed.

No demonstration [being made] on the morning of January 1, Crittenden was ordered to occupy the point opposite the ford, on his left, with a brigade.

About 2 o’clock in the afternoon, the enemy, who had shown signs of movement and massing on our right, appeared at the extremity of a field 1½ miles from the Murfreesborough pike, but the presence of Gibson’s brigade, with a battery, occupying the woods near Overall’s Creek, and Negley’s division, and a portion of Rousseau’s, on the Murfreesborough pike, opposite the field, put an end to this demonstration, and the day closed with another demonstration by the enemy on Walker’s brigade, which ended in the same manner.

On Friday morning the enemy opened four heavy batteries on our center, and made a strong demonstration of attack a little farther to the right, but a well-directed fire of artillery soon silenced his batteries, while the guns of Walker and Sheridan put an end to his efforts there.

About 3 p.m., while the commanding general was examining the position of Crittenden’s left across the river, which was now held by Van Cleve’s division, supported by a brigade from Palmer’s, a double line of skirmishers was seen to emerge from the woods in a southeasterly direction, advancing across the fields, and they were soon followed by heavy columns of infantry, battalion front, with three batteries of artillery. Our only battery on that side of the river had been withdrawn from an eligible point, but the most available spot was pointed out, and it soon opened fire upon the enemy. The line, however, advanced steadily to within 100 yards of the front of Van Cleve’s division, when a short and fierce contest ensued. Van Cleve’s division, giving way, retired in considerable confusion across the river, followed closely by the enemy.

General Crittenden immediately directed his chief of artillery to dispose the batteries on the hill on the west side of the river so as to open on them, while two brigades of Negley’s division, from the reserve, and the Pioneer Brigade, were ordered up to meet the onset. The firing was terrific and the havoc terrible. The enemy retreated more rapidly than they had advanced. In forty minutes they lost 2,000 men.

General Davis, seeing some stragglers from Van Cleve’s division, took one of his brigades and crossed at a ford below, to attack the enemy on his left flank, and, by General McCook’s order, the rest of his division was permitted to follow; but, when he arrived, two brigades of Negley’s division and Hazen’s brigade, of Palmer’s division, had pursued the fleeing enemy well across the fields, capturing four pieces of artillery and a stand of colors.

It was now after dark, and raining, or we should have pursued the enemy into Murfreesborough. As it was, Crittenden’s corps passed over, and, with Davis’, occupied the crests, which were intrenched in a few hours.

Deeming it possible that the enemy might again attack our right and center, thus weakened, I thought it advisable to make a demonstration on our right by a heavy division of camp-fires, and by 1aying out a line of battle with torches, which answered the purpose.

Saturday, January 3. it rained heavily from 3 o’clock in the morning. The plowed ground over which our left would be obliged to advance was impassable for artillery. The ammunition trains did not arrive until 10 o’clock. It was, therefore, deemed unadvisable to advance; but batteries were put in position on the left, by which the ground could be swept, and even Murfreesborough reached by Parrott shells.

A heavy and constant picket firing had been kept up on our right and center, and extending to our left, which at last became so annoying that in the afternoon I directed the corps commanders to clear their fronts.

Occupying the wood to the left of Murfreesborough pike with sharpshooters, the enemy had annoyed Rousseau all day, and General Thomas and himself requested permission to dislodge them and their supports, which covered a ford. This was granted, and a sharp fire from four batteries was opened for ten or fifteen minutes, when Rousseau sent two of his regiments, which, with Spears’ Tennesseans and the Eighty-fifth Illinois Volunteers, that had come out with the wagon-train, charged upon the enemy, and, after a sharp contest, cleared the woods and drove the enemy from his trenches, capturing from 70 to 80 prisoners.

Sunday morning, January 4, it was not deemed advisable to commence offensive movements, and news soon reached us that the enemy had fled from Murfreesborough. Burial parties were sent out to bury the dead, and the cavalry was sent to reconnoiter.

Early Monday morning General Thomas advanced, driving the rear guard of rebel cavalry before him 6 or 7 miles toward Manchester. McCook’s and Crittenden’s corps following, took position in front of the town, occupying Murfreesborough.

We learned that the enemy’s infantry had reached Shelbyville by 12 m. on Sunday, but, owing to the impracticability of bringing up supplies, and the loss of 557 artillery horses, farther pursuit was deemed inadvisable.

It may be of use to give the following general summary of the operations and results of the series of skirmishes closing with the battle of Stoners River and occupation of Murfreesborough:

We moved on the enemy with the following forces: Infantry, 41,421; artillery, 2,223; cavalry, 3,296. Total, 46,940.

We fought the battle with the following forces: Infantry, 37,977; artillery, 2,223; cavalry, 3,200. Total, 43,400.

We lost in killed: Officers, 92; enlisted men, 1,441; total, 1,533. Wounded: Officers, 384; enlisted men, 6,861; total, 7,245. Total killed and wounded, 8,778, being 20.03 per cent. of the entire force in action. O

ur loss in prisoners is not fully made out, but the provost-marshal-general says, from present information, they will fall short of 2,800.

If there are many more bloody battles on record, considering the newness and inexperience of the troops, both officers and men, or if there has been more true fighting qualities displayed by any people, I should be pleased to know it.

As to the condition of the fight, we may say that we operated over an unknown country, against a position which was 15 per cent. better than our own, every foot of ground and approaches being well known to the enemy, and that these disadvantages were fatally enhanced by the faulty position of our right wing.

The force we fought is estimated as follows:

We have prisoners from one hundred and thirty-two regiments of infantry (consolidations counted as one), averaging from those in General Bushrod Johnson’s division 411 each, say, for certain, 350 men each, which will give–

132 regiments of infantry, say 350 men each 46,200 12 battalions of sharpshooters, say 100 men each 1,200 23 batteries of artillery, say 80 men each 1,840 29 regiments of cavalry, say 400 men each, and 24 organizations of cavalry, say 70 men each 13,250 62,490

Their average loss, taken from the statistics of Cleburne’s, Breckin-ridge’s, and Withers’ divisions, was about 2,080 each. This, for six divisions of infantry and one of cavalry, will amount to 14,560 men, or to ours nearly as 165 to 100.

Of 14,560 rebels struck by our missiles, it is estimated that 20,000 rounds of artillery hit 728 men; 2,000,000 rounds of musketry hit 13,832 men, averaging 27.4 cannon-shots to hit 1 man; 145 musket-shots to hit 1 man.

Our relative loss was as follows: Right wing, 15,933 musketry and artillery; loss, 20.72 per cent. Center, 10,866 musketry and artillery; loss, 18.4 per cent. Left wing, 13,288 musketry and artillery; loss, 24.6 per cent.

On the whole, it is evident that we fought superior numbers on unknown ground; inflicted much more injury than we suffered; were always superior on equal ground with equal numbers, and failed of a most crushing victory on Wednesday by the extension and direction of our right wing.

This closes the narrative of the movements and seven days’ fighting which terminated with the occupation of Murfreesborough. For a detailed history of the parts taken in the battles by the different commands, their obstinate bravery and patient endurance, in which the new regiments vied with those of more experience, I must refer to the accompanying sub-reports of the corps, division, brigade, regimental, and artillery commanders.

Besides the mention which has been already made of the services of our artillery by the brigade, division, and corps commanders, I deem it a duty to say that such a marked evidence of skill in handling the batteries, and in firing low and with such good effect, appears in this battle to deserve special commendation.

Among the lesser commands which deserve special mention for distinguished services in the battle the Pioneer Corps, a body of 1,700 men, composed of details from the companies of each infantry regiment, organized and instructed by Capt. James St. Clair Morton, Corps of Engineers, chief engineer of this army, which marched as an infantry brigade with the left wing, making bridges at Stewart’s Creek; prepared and guarded the ford at Stone’s River on the night of the 29th and 30th; supported Stokes’ battery, and fought with valor and determination on the 31st, holding its position till relieved on the morning of the 2d; advancing with the greatest promptitude and gallantry to support Van Cleve’s division against the attack on our left on the evening of the same day, constructing a bridge and batteries between that time and Saturday evening. The efficiency and esprit du corps suddenly developed in this command, its gallant behavior in action, and the eminent services it is continually rendering the army, entitle both officers and men to special public notice and thanks, while they reflect the highest credit on the distinguished ability and capacity of Captain Morton, who will do honor to his promotion to a brigadier-general, which the President has promised him.

The ability, order, and method exhibited in the management of the wounded elicited the warmest commendations from all our general officers, in which I most cordially join. Notwithstanding the numbers to be cared for, through the energy of Dr. Swift, medical director, ably assisted by Dr. Weeds and the senior surgeons of the various commands, there was less suffering from delay than I have ever before witnessed.

The Tenth Regiment of Ohio Volunteers, at Stewart’s Creek, Lieut. Col. J. W. Burke commanding, deserves especial praise for the ability and spirit with which they held that post, defended our trains, succored their guards, chased away Wheeler’s rebel cavalry, saving a large wagon-train, and arrested and retained for service stragglers from the battlefield.

The First Regiment of Michigan Engineers and Mechanics, at La Vergne, under the command of Colonel Innes, fighting behind a slight protection of wagons and brush, gallantly repulsed a charge from more than ten times their number of Wheeler’s cavalry.

For distinguished acts of individual zeal, heroism, gallantry, and good conduct, I refer to the accompanying lists of special mentions and recommendations for promotion, wherein are named some of the many noble men who have distinguished themselves and done honor to their country and the starry symbol of its unity. But those named there are by no means all whose names will be inscribed on the rolls of honor we are preparing, and hope to have held in grateful remembrance by our countrymen.

To say that such men as Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, true and prudent, distinguished in council and on many a battle-field for his courage, or Major-General McCook, a tried, faithful, and loyal soldier, who bravely breasted the battle at Shiloh and at Perryville, and as bravely on the bloody field of Stone’s River, and Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden, whose heart is that of a true soldier and patriot, and whose gallantry, often attested by his companions in arms on other fields, witnessed many times by this army long before I had the honor to command it, and never more conspicuously than in this combat, maintained their high character throughout this action, but feebly expresses my feeling of obligation to them for counsel and support from the time of my arrival to the present hour. I doubly thank them, as well as the gallant and ever-ready Major-General Rousseau, for their support in this battle.

Brig. Gen. D. S. Stanley, already distinguished in four successful battles–Island No. 10; May 27, before Corinth; Iuka, and the battle of Corinth–at this time in command of our ten regiments of cavalry, fought the enemy’s forty regiments of cavalry, and held them at bay, or beat them wherever he could meet them. He ought to be made a major-general for his service, and also for the good of the service.

As for such brigadiers as Negley, Jefferson C. Davis, Johnson, Palmer, Hascall, Van Cleve, Wood, Mitchell, Cruft, and Sheridan, they ought to be major-generals in our service. In such brigade commanders as Colonels Carlin, Miller, Hazen, Samuel Beatty, of the Nineteenth Ohio; Gibson, Grose, Wagner, John Beatty, of the Third Ohio; Harker, Starkweather, Stanley, and others, whose names are mentioned in the accompanying reports, the Government may well confide. They are the men from whom our troops should at once be supplied with brigadier-generals; and justice to the brave men and officers of the regiments equally demand their promotion to give them and their regiments their proper leaders. Many captains and subalterns also showed great gallantry and capacity for superior commands. But, above all, the sturdy rank and file showed invincible fighting courage and stamina, worthy of a great and free nation, requiring only good officers, discipline, and instructions to make them equal, if not superior, to any troops in ancient or modern times. To them I offer my most heartfelt thanks and good wishes. Words of mine cannot add to the renown of our brave and patriotic officers and soldiers who fell on the field of honor, nor increase respect for their memory in the hearts of our countrymen.

The names of such men as Lieut. Col. J.P. Garesche, the pure and noble Christian gentleman and chivalric officer, who gave his life an early offering on the altar of his country’s freedom; the gentle, true, and accomplished General Sill; the brave, ingenuous, and able Colonels Roberts, Milliken, Schaefer, McKee, Read, Forman, Fred. Jones, Hawkins, Kell, and the gallant and faithful Major Carpenter, of the Nineteenth Regulars, and many other field officers, will live in our country’s history, as will those of many others of inferior rank, whose soldierly deeds on this memorable battle-field won for them the admiration of their companions, and will dwell in our memories in long future years, after God, in his mercy, shall have given us peace, and restored us to the bosom of our homes and families.

Simple justice to the gallant officers of my staff, the noble and lamented Lieutenant-Colonel Garesche, chief of staff; Lieutenant-Colonel Taylor, chief quartermaster; Lieutenant-Colonel Simmons, chief commissary; Maj. C. Goddard, senior aide.de-camp; Maj. Ralston Skinner,judge-advocate-general; Lieut. Frank S. Bond, aide-de-camp of General Tyler; Capt. Charles R. Thompson, my aide-de-camp; Lieut. Byron Kirby, Sixth U.S. Infantry, aide-de-camp, who was wounded on the 31st; R. S. Thorns, esq., a member of the Cincinnati bar, who acted as volunteer aide-de-camp, behaved with distinguished gallantry; Colonel Barnett, chief of artillery and ordnance; Capt. J. H. Gilman, Nineteenth U.S. Infantry, inspector of artillery; Capt. James Curtis, Fifteenth U.S. Infantry, assistant inspector-general; Captain Wiles, Twenty-second Indiana, provost-marshal-general; Captain Michler, chief of Topographical Engineers; Capt. Jesse Merrill, Signal Corps, whose corps behaved well; Capt. Elmer Otis, Fourth Regular Cavalry, who commanded the courier line connecting the various headquarters most successfully, and who made a most opportune and brilliant charge on Wheeler’s cavalry, routing a brigade and recapturing 300 of our prisoners; Lieutenant Ed-son, United States ordnance officer, who, during the battle of Wednesday, distributed ammunition under the fire of the enemy’s batteries, and behaved bravely; Captain Hubbard and Lieutenant Newberry, who joined my staff on the field and acted as aides, rendered valuable service in carrying orders on the field; Lieut. E.G. Roys, Fourth U.S. Cavalry, who commanded the escort of the headquarters train, and distinguished himself for gallantry and efficiency–all not only performed their appropriate duties to my entire satisfaction, but, accompanying me everywhere, carrying orders through the thickest of the fight, watching while others slept, and never weary when duty called, deserve my public thanks and the respect and gratitude of the army.

With all the facts of the battle fully before me, the relative numbers and positions of our troops and those of the rebels, the gallantry and obstinacy of the contest and the final result, I say, from conviction, and as public acknowledgment due to Almighty God, in closing this report, “Non nobis Domine! non nobis sed nomini tuo da gloriam.”

W. S. ROSECRANS, Major-General, Commanding.